Exploring Pneuma: A Conversation with Barbara Campbell Thomas

Barbara Campbell Thomas's solo exhibition Pneuma is on display in the Ruffin Gallery through December 18, 2020. In conjunction with her exhibition, Ruffin Gallery Assistant, Olivia Pettee, sat down with Barbara to talk about her process, inspiration, and thoughts behind her show.

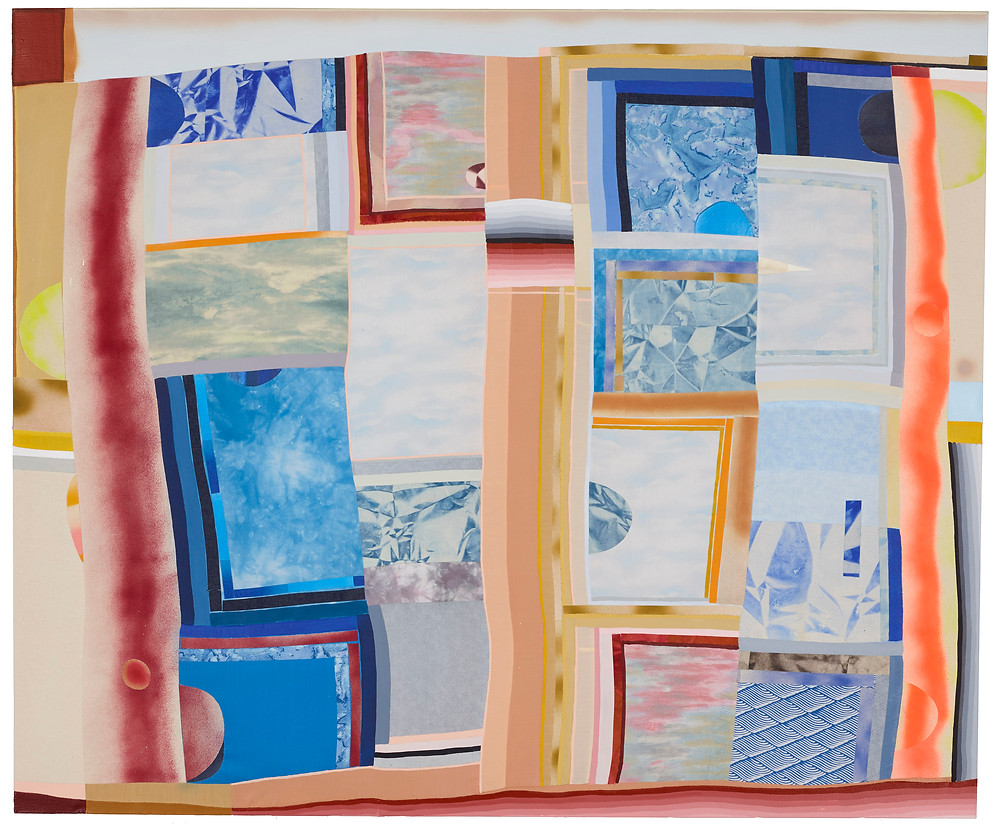

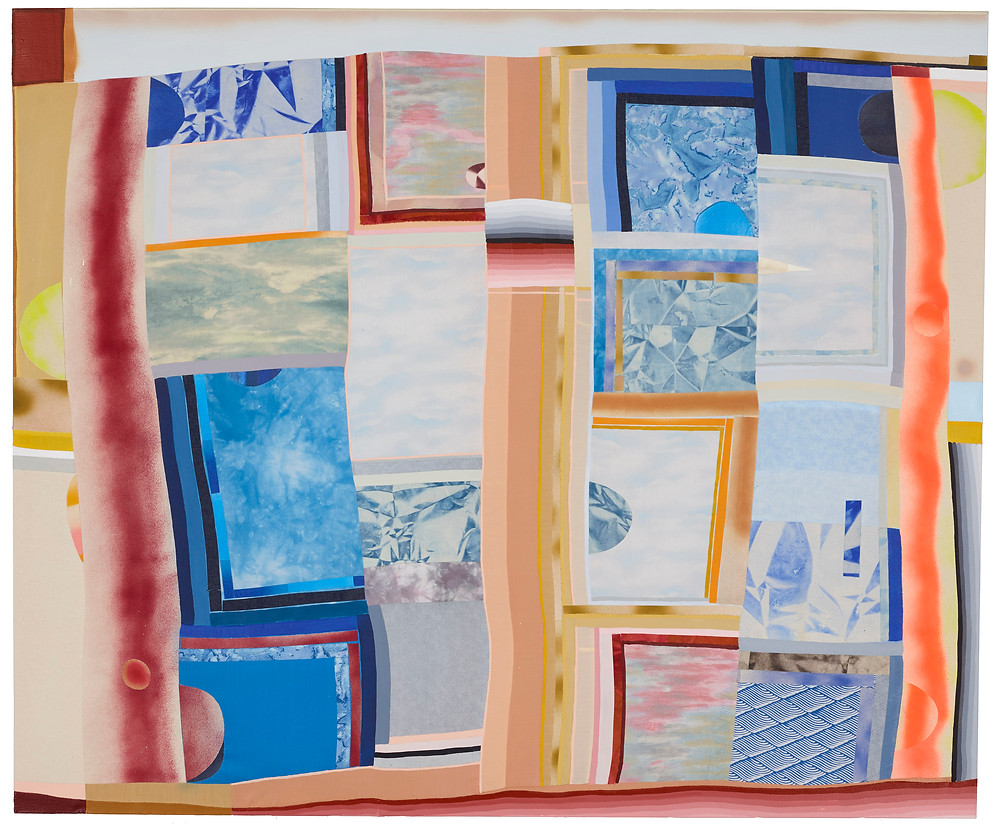

Barbara Campbell Thomas, Manner of Infinite Forms, 2019. Acrylic and collage on canvas with sewn fabric. Courtesy the artist. Right: detail, Barbara Campbell Thomas, Manner of Infinite Forms, 2019, acrylic and collage on canvas with sewn fabric.

The title of your exhibition and one of the pieces is Pneuma. Where does this title come from, and what does it mean in relation to your work?

It is an ancient Greek word actually, and it basically means ‘air in motion’ or ‘breath’ as something necessary to life. The title also stems from one painting in the show that is called Pneuma. The painting has all these triangles that are oriented in different directions. I called it Pneuma because the painting felt as though it was really imaging this sort of opening and closing, or a kind of inhalation and exhalation.

Related to the title and to inhalation and exhalation is the fact that the first layer of these paintings is a piece of fabric (canvas and other kinds of fabric) that is pieced and sewn together. When I stretch that initial layer over the stretcher bars, the act of stretching softens the geometry. So, for instance, a square almost looks like it becomes inflated. When the softened geometry began to emerge, it felt to me as though the shapes were starting to breath. Something I think about is the notion of the act of painting as being a kind of elemental human activity that has the capacity to engage the material and the immaterial, with body and spirit. My paintings are abstract so they aren't really pictures of things, per se. They're really more about a state of being. I am a physical being, and my engagement with paint, with painting, is an intensely physical act. But it is the physical engagement with material that has the potential to move into immaterial realms of inquiry. This has always been my experience as a painter. So, this notion of breath, and the way in which breath has the capacity to ground oneself, while also giving one life is also something I've been thinking about a lot. How does painting connect to breath?

How did you come to the technique of sewing?

It's been within the last six years or so that sewing started to become important to me artistically. In the last three years, I've begun to integrate it into painting. My connection to sewing really comes from my mother who is a quilter, and she taught me how to quilt in 2014.

When she was teaching me, I was immediately attracted to what is called piecing, which is where you're taking shapes and setting them side by side and sewing them together which creates that seam. I quickly started to see that this sewing could be the ground of the painting itself. I experimented for a while to see how shapes were transformed through the act of stretching the fabric. The sewn layer felt so rich; it almost felt like a missing part of the work was suddenly present. In addition to the painting and sewn aspects of the work, collage is a critical element. All three of those—paint, fabric and collage—work in relation to each other over the surface of my paintings.

I also really love the ways in which the history of quilting is so linked to a history of a female makers, and so I am intrigued with the way that that expands how I see painting.

I think that's one of the first things I noticed when I saw your work: how really layered it feels and the way the layers interact through color. What are some of your inspirations as far as color?

Color is an intuitive visual language for me. I attended a talk given by the artist Jessica Stockholder. She said, “Making is a kind of thinking.” I’ve never forgotten those words. For me, working with the interplay of colors is a kind of thinking. My color palettes slowly shift over time, and I feel as though they're informed by me just living my life, taking in what I see, digesting it all. I think that in the act of painting there’s a filtering process and certain colors seem to emerge in concert.

How do your notebooks and sketchbooks speak in conversation with some of your larger work and what role have your sketchbooks played in the evolution of your practice?

My sketchbooks always predict what's going to come. They are really a point in the overall studio practice that is explicitly about exploration and experimentation. I try to not limit myself in terms of what I'm willing to do in my sketchbooks. So, at times pages can seem strange to me or feel as though they are emerging out of left field. But the sketchbooks are a place where I just allow anything to emerge, whether it's logical or illogical. Because I've learned over time that something that I don't understand now may make sense in a couple of months or years. The sketchbooks are the place where the next steps of the paintings show up first. Currently, there's a strong linear aspect in play in my paintings and that emerged as line drawings in my sketchbooks.

I noticed a lot of quotes in your notebooks. In past interviews, you've touched on how your work is inspired by the writings of mystics.

I am an abstract painter and I've been an abstract painter for a long time now. For me, that engagement with abstraction is so much about a commitment to exploring ways of giving form to what is unsayable. A big part of that has been an investigation of the spiritual aspects of who we are as humans. I’ve found painting to be a perfect medium to think about what it means to be a physical being, as I talked about earlier. I read a lot of theology based in mysticism. While my base is in the Christian mystical tradition of writers such as St. John of the Cross, Teresa of Avila and Thomas Merton, the mystical traditions of all the world's religions are fascinating to me, so I also read a lot of writings by Buddhists and the Sufi mystics. There is so much cross conversation between all of these traditions.

The notebooks are a place where I gather the words I want to think and ponder more. The notebooks are so valuable for me as they're such an intense record of my thinking. And materially, they are actually a collaboration with my mother because she makes the covers. She buys the sketchbooks, creates the covers, and then sends them to me to fill: a literal threading between generations, between women.

When did you start making sketchbooks?

I started keeping sketchbooks when I was in college and I still have all of them. I graduated in 1998, so that is over 20 years of sketchbook investigation. My sketchbooks have transformed in different ways. I would say the notebooks from the last five or six years are a real flowering of what the notebooks are supposed to be, as I understand the role of the notebooks better now in relation to my overall studio practice. They're an integral part of who I am as an artist.

How did you get to establishing your artistic identity? Were there any sort of pivotal moments or challenges that you faced?

When I was an undergraduate student, I moved from working with representational imagery to abstraction in my junior year, and that shift was so important. I remember I had a really important studio visit with a painter, and through the things that she said I realized that I was holding the ideas I was working with too tightly. It was almost like when you hold sand tightly in your hands, and of course it just all falls away. I realized I had to get at the ideas that I was thinking about as though I was coming in through the back door. I needed to get at my ideas at a more oblique angle, so abstraction started to make a lot more sense to me. It felt freer and more open for me.

2005, when my first son was born, was another really important moment. It coincided with a real shift in my practice that was connected to an existential “Who am I now that I'm a mother? And, what does that mean?” It just initiated this intense period of self-reflection at a moment when there was much less time to make work. That was also a hard time because I had to redefine what it meant for me to be an artist. That actually is when my interest in collage and working with fragments and bits and pieces that gather over time really become cemented.

Were there any artists or work in particular that you were inspired by as far as collaging goes as a transition into creating more abstract work?

I received my undergraduate degree at Penn State, and my painting teacher was a woman named Helen O'Leary. She is an abstract painter who really plays with the definition of painting. I really became a painter because of her. I took beginning painting with her and she was just able to convey the sense that painting could be anything. There was this incredible sense of possibility that was connected with the medium and I became intoxicated with the idea of being involved in making paintings. She continues to be an inspiration and a mentor for me in a lot of ways.

I had another opportunity in graduate school to work with an artist named Judy Pfaff who is an installation artist. I was an artist assistant for her and lived with her for a summer. Nothing was impossible to her. There was just this way in which she was so ambitious, but also so generous. I guess that’s a thread for me: people who are able to convey the ways in which there are no limits. We have to take those limits away from ourselves and from the things that we do and make.

What advice would you give to aspiring artists or those who are interested in making multimedia work?

I think I would stress the importance of experimenting and allowing yourself to try new things. I always try to get my students to inquire into the ways that we put limits on ourselves. What are the ways that we’re telling ourselves, “oh, I'm this kind of artist or, you know, I do this but I don't do that.” There are ways in which figuring out who we are, of course, is a process of figuring out what we like and what we don't like. But there's also this way in which we have to start to inquire into what are the limitations we place on ourselves that are closing out possibility and what are the limitations that we place on ourselves that are opening up possibility. I think that requires a lot of self-reflection and willingness to look yourself squarely in the eye and say “okay, am I being honest? And, where am I being dishonest with myself?” I think making a lot of work is a great way to figure out who you are. You just have to make a lot of work and sometimes a lot of it is going to be bad, and that's okay. I think we live in a culture that doesn't know what to do with failure. You have to engage with failure as an artist at any age because that is the way in which you figure out what's working and what's not.

To make a reservation to view the exhibition, visit here!

For more information on Barbara's work, check out her website.